DOWNLOAD

Submit the form below to continue your download

SUCCESS

Your download will begin shortly

BIO

Jonah is the Head of External Affairs and Impact at Generate where he oversees our communications, government engagement, and impact assessment and strategy.

Prior to Generate, Jonah led Breakthrough Energy a network founded by Bill Gates including investment funds, nonprofit and philanthropic programs, and policy efforts linked by a common commitment to scale the technologies we need to achieve a path to net zero emissions by 2050. During that time, he also served as Mr. Gates’s senior advisor for policy and government relations. Prior to Breakthrough Energy, Jonah spent nearly 15 years in Washington, D.C., leading integrated advocacy, communications, and grassroots campaigns. He led a series of policy efforts on a variety of issues – from civil rights to education reform to nuclear non-proliferation. Before that, he served as primary spokesperson and chief strategist for the largest national campaign to protect voting rights. Jonah holds a J.D. degree from Boston College Law School and a B.A. degree in History from Binghamton University. Jonah lives in Seattle with his wife Jackie and his two children, Desmond and Fiona.

Comfort in the chaos

June 2024 has been the most destabilizing political period in the US for at least the last 55 years. The global political situation is not much more settled.

Expert View By Jonah Goldman and Logan Goldie-Scot

BIO

Jonah is the Head of External Affairs and Impact at Generate where he oversees our communications, government engagement, and impact assessment and strategy.

Prior to Generate, Jonah led Breakthrough Energy a network founded by Bill Gates including investment funds, nonprofit and philanthropic programs, and policy efforts linked by a common commitment to scale the technologies we need to achieve a path to net zero emissions by 2050. During that time, he also served as Mr. Gates’s senior advisor for policy and government relations. Prior to Breakthrough Energy, Jonah spent nearly 15 years in Washington, D.C., leading integrated advocacy, communications, and grassroots campaigns. He led a series of policy efforts on a variety of issues – from civil rights to education reform to nuclear non-proliferation. Before that, he served as primary spokesperson and chief strategist for the largest national campaign to protect voting rights. Jonah holds a J.D. degree from Boston College Law School and a B.A. degree in History from Binghamton University. Jonah lives in Seattle with his wife Jackie and his two children, Desmond and Fiona.

BIO

Logan Goldie-Scot is Head of Research at Generate Capital, responsible for building and communicating the firm’s information advantage. He is focused on developing proprietary insights relating to Generate’s six core sectors, while supporting market-wide coverage and origination efforts.

Prior to Generate, Logan joined BloombergNEF in 2010 and was Head of Clean Power research when he left in 2022. This was a 30-person group spanning solar, wind, energy storage and power grids. At BloombergNEF he previously worked as a solar analyst, built and led the Energy Storage team, and developed the firm’s first clean energy Index and ETF, in collaboration with Goldman Sachs. Logan is a regular writer, speaker and conference panellist on topics relating to the energy transition. He has an MA (Hons) in Arabic from Edinburgh University and in 2019 completed executive training in Supply Chain Management at Stanford GSB.

The policy drivers for the energy transition are new enough that this kind of disruption sparks questions about the durability of the capital, projects, technology development, and deployment of the infrastructure we need to decarbonize in the event of a political shift. But while there are significant differences in the priorities for the energy transition across the political spectrum, there is some signal in the deafening noise of the 2024 election cycle pointing to the transition’s resilience regardless of outcomes. There is some comfort in the chaos.

The current administration has passed the most ambitious climate legislation in the country’s history, helping make progress toward the country’s climate goals and revitalize the manufacturing sector. A continuation of this administration, under VP Harris, will likely focus on expanding opportunities for new markets and reinforcing current fledgling markets within the sector. Expect a concerted effort to perfect some of the elements of the IRA, including expanding the technology coverage to areas such as industrial decarbonization, and extending the duration of the IRA’s incentives.

The bigger question is: What happens if the administration changes to one more hostile to the energy transition?

The rumors of the death of the IRA are likely overblown. Many elements of the energy transition, including those we focus on at Generate, are largely insulated from a change of US administrations. Meaningful signals indicate that renewable power, decarbonization of large-scale mobility, waste, and much of the industrial decarbonization equation will be maintained through political changes. The most powerful stakeholders across the public and private sectors are aligned on the energy transition, and their support will be difficult for any administration to ignore. Where federal support has been critical to the economics of projects, we believe that rulemaking is advanced enough and bipartisan congressional support deep enough that rollbacks are unlikely. That belief is reinforced by Congressional activity during the last Republican administration and bolstered by Republican congressional action over the past two years since the IRA was signed into law. Consider a few key factors:

- Jobs: The build-out of sustainable infrastructure over the last decade has created critical employment opportunities and a meaningful increase in domestic manufacturing that we believe will remain a priority under any political leadership.

- Communities Count: Most important, of course, is the real world benefits IRA-backed projects are yielding. While politics certainly seem less local than when Tip O’Neil made his famous quip, it is still “the economy, stupid” and people judge the success of their elected officials by the things they see in their communities. Over 60% of announced projects that benefit from some form of federal resources and over 80% of capacity in new renewables and storage projects in the late stage of development are in communities represented by Republicans.

- Corporate Demand: Corporate purchasing decisions and commitments have driven billions into clean infrastructure, creating industry tailwinds that have been strengthened by consumer demand and aggressive goals from the largest data providers. Moreover, the last time the federalgovernment was hostile to climate, it spurred some of the most ambitious private sector commitments to satisfy a clear and addressable demand from employees, shareholders, customers, and managers.

- International Obligations: The recent elections in India, Europe, the UK, and France – as analyzed in this newsletter – have largely maintained the status quo of climate commitments. That includes the increasing oversight governments hold over investors to enable clean energy infrastructure investments. A prominent example is Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). Some of the most aggressive investors in the US and around the world are governed by such obligations, seek consistency across them, and are building their global investment strategies around them.

- Subnational Policy: A network of state and local policy drivers has emerged as critical in making clean energy projects pencil, from clean fuel standards to building codes and procurement. A federal regime more hostile to climate will likely see a more substantial counter-reaction from other motivated policy makers at the non-federal level to incorporate all elements of policy power – money, tax-based incentives, purchasing power, oversight, and policy design – to continue the energy transition at the state and local levels.

That is not to say a change in administration is unimportant to the transition. A new administration and a Republican-controlled Congress could bring adjustments to, but not a full repeal of, IRA energy incentives. And much beyond the IRA remains at stake: New programs and incentives will stall, and global, multilateral actions toward climate progress would be dramatically weakened. We would expect to see executive actions that withdraw the US from the Paris Climate Accord, reverse President Biden’s numerous climate and clean energy executive orders, and downsize Federal agency climate functions and staff.

The bottom line, though, is clear: the energy transition is too big to stop. After the dust of this election cycle has settled, durable and reliable investment avenues will remain.

A View From London

The Labour Party won by a landslide in the UK General Election in early July, gaining 200 parliament seats and giving it a total of 411 in the House of Commons compared to a simple majority of 326. After 14 years in power and five prime ministers, the Conservative Party lost over two-thirds of its seats, reducing its total to just 121.

Labour’s victory is a boon for the country’s climate outlook. The election results were primarily a reflection of electoral fatigue with an increasingly incompetent and tired government. Nonetheless, climate change was identified as the fifth most important issue to voters, after cost of living, health, the broader economy, and immigration (YouGov, Carbon Brief).

Emissions dropped 65% under Conservative party rule from 2010 to 2023, as the country all but phased out coal (Ember). Offshore wind took off under its watch, with cumulative installations rising from 1.3GW in 2010 to 15GW in 2024 (BloombergNEF), and EV sales accounted for 25% of new passenger vehicle sales in 2023. Despite this progress, the Conservative Party rolled back many of its climate ambitions in recent years and stymied development of onshore wind. It went into the campaign advocating for a slower transition, although not a reversal by any means, emphasizing the need to balance costs and priorities (Cleaning Up podcast).Labour by contrast leant in.

Labour is targeting zero-carbon power by 2030, requiring a massive increase in wind and solar capacity, alongside more nuclear. It will restore the ban on internal combustion vehicle sales by 2030 and has already lifted a de facto ban on onshore wind. It will also commit GBP 8.3 billion to capitalize Great British Energy (gov.uk), a publicly owned company to invest in clean energy. The clean power company’s pitch was “lower bills, energy security, good jobs” (Figure 1). This aligns with a marked change in the framing of the energy transition elsewhere: a recent messaging toolkit in the US advises Democrat lawmakers to champion their climate achievements without mentioning the IRA by name, and to avoid terms like “net zero” and “1.5° Celsius” in favor of “jobs,” “investment,” “extreme weather,” and “pollution” (PoliticoPro 🔒).

Ambitious 2030 goals are easy to dismiss as unrealistic based on the nitty gritty of development, permitting, interconnection, and life in general. The ambitions are however a clear statement of intent from the world’s sixth largest economy, which has to date proven adept at decarbonization. The change in framing also helps to make decarbonization efforts more durable. Even if part of what explains the shift is near-term political marketing (see What we’re reading), it is also a recognition of the inevitability of the energy transition.

A View From Paris

The left-wing New Popular Front alliance, launched in June of this year, secured 188 seats in the National Assembly, while French President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist alliance Ensemble came in second place with 161 seats (Politico). The far-right National Rally and its allies, which won by a clear margin in the first round of voting for the National Assembly in France, came in third with 142 seats. No party holds a majority and President Macron has asked Prime Minister Gabriel Attal to stay on in an interim capacity until there is more clarity over a governing coalition.

The uncertain political outlook makes it hard to precisely pin down the climate impact quite yet. But it’s clear that the result is better than if the National Rally had won: the party supported a ban on new wind and solar, even extending to repowering; opposed bans for ICE vehicles and fossil fuel boilers; and critiqued the low emissions zones in place around many French cities. Ensemble’s framing of climate change by contrast: “full employment, reindustrialization, ecology” (Carbon Brief).

A View From Brussels

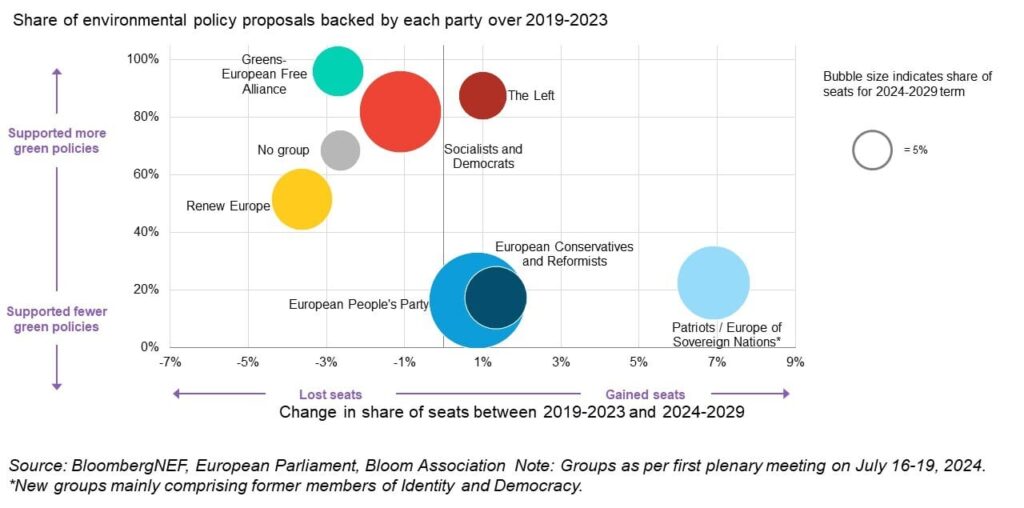

The June 2024 election of the European Parliament resulted in a swing to the political right. Left-leaning political groups, which have backed more ambitious climate policy, saw their share of seats fall from 50% to 42% (Figure 3, BloombergNEF).

The last EU parliament passed the European Green Deal, with more tangible reforms laid out under the Fit for 55 framework. There is limited support to unwind these. The political right’s gains will, however, make it harder to deliver on new climate initiatives such as the February 2024 Commission recommendation for a 90% reduction in emissions by 2040.

In mid-July, Ursula von der Leyen secured a second term as European Commission president. Her policy program threaded a needle to appeal to both environmentalists and her own centrist-right political family, the European People’s Party (EPP). She framed green policies as measures to boost the economy and security, warning “Those who stand still will fall behind. Those who are not competitive will be dependent.” Forinstance, she reaffirmed her commitment to the existing Green Deal targets and aims to enshrine the 90% emissions reduction into law, but now as part of the Industrial Clean Deal (PoliticoPro 🔒). Words matter.

Contributors

Jonah Goldman

Head of External Affairs and Impact

Logan Goldie-Scot

Director of Market Research

SECTIONS

More insights

Why the infrastructure transition needs creative credit

Private credit has stepped in to help fill some of the biggest gaps in our capital markets in recent years.

Read moreAn Inflection Point for LCFS

LCFS: California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) program catapulted the state’s decarbonization progress, but policy updates are needed for the program to remain a critical market creator for decarbonization technologies.

Read moreComfort in the chaos

The policy drivers for the energy transition are new enough that this kind of disruption sparks questions about the durability of the capital, projects, technology development, and deployment of the infrastructure we need to decarbonize in the event of a political shift. But while there are significant differences in the priorities for the energy transition across

Read more